Sphere Flyer

Hidden in a dark crevice, on a scree slope of the Antarctic Peninsula, Skipjack is about to hatch. A dusky Wilson’s storm petrel, his mother stands on her webbed toes, making room for his large rocking egg. A hooked bill, almost as long as her own, breaks through the shell. Chipping away, it stops and starts, this black tube-shaped bill. Moments later a sopping chick breaks free.

The small mother preens the newcomer and, although ravenous, she settles down over him to brood. Three days have passed since her mate took his turn nesting the egg.

Suddenly she hears fluttering wings and a short coo outside the rocky tunnel in the scree. Skipjack’s father has come.

The new father flounders to her from the narrow dim tunnel leading to the outside world. His eyes adjust. Skipjack’s mother emits her soft short peep. She cocks her head to receive his father’s offering of partly digested seafood. Then she steps clumsily off the newly hatched storm petrel. She plucks up some bits of shell and disappears up the narrow tunnel out of darkness into light.

Father regurgitates still more musky-smelling seafood down his offspring’s gullet. He covers Skipjack with his own warm body, tucks his head beneath a wing and promptly sleeps.

For some days mother and father take turns skimming up seafood and brooding the chick, who is soon bigger and fatter than his parents. Through unflagging care and feeding, Skipjack has become so fat he can scarcely move.

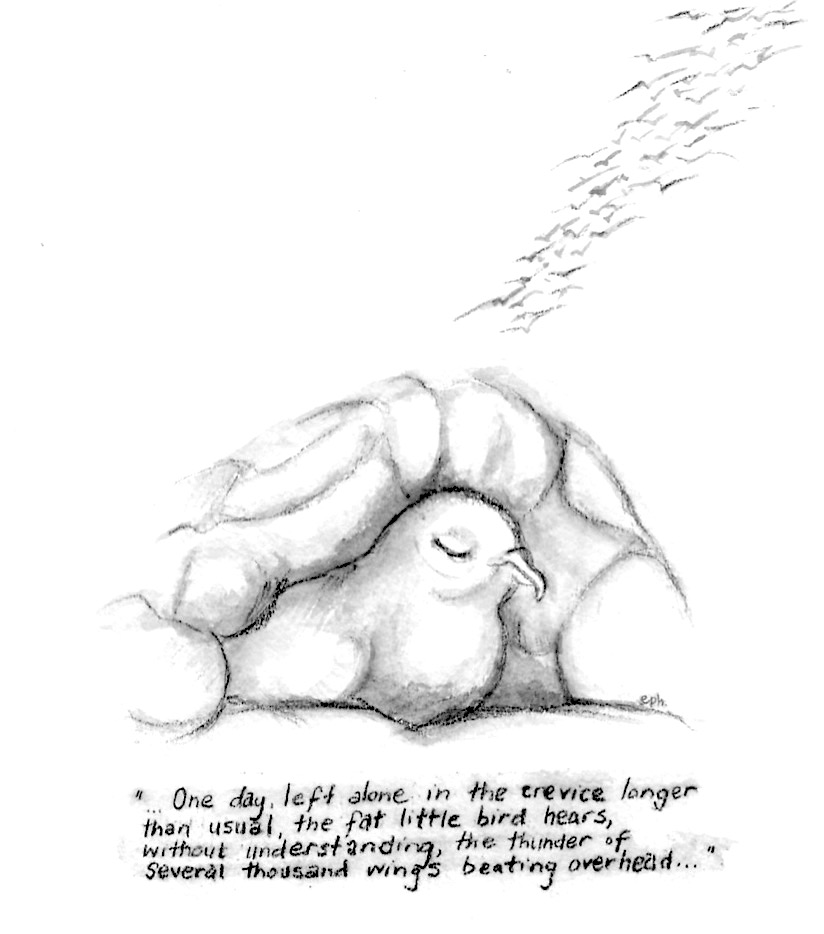

One day he is left alone longer than usual. Listening for mother and father, he hears the thunder of hundreds of thousands—a multitude of wings beating overhead outside. Now all is profoundly silent.

He waits and waits for mother or father to come down the dark tunnel. Then again he nests in the darkness of these rocks, dozing. Dozing and waking, the fat little bird waits but his parents do not come. Skipjack has never even seen the sky. And he is so fat he can’t get up the tunnel. How will he ever find the light?

Troubled and uneasy, he sends lonely peeps into the cramped darkness. But by the fifth day, Skipjack’s forced fast has diminished his body fat. He scrambles around in the crevice. A fierce storm passes overhead, sending whistling drafts down the tunnel to chill his now slender fledgling body. Even his soft down has been replaced. Flight feathers must now hold warmth closely, for all his fat is gone.

The storm beats on and he trembles beneath the scree. Then the blizzard passes off and in its wake come curiously happy sounds. Skipjack hears muted coos, chuckles, squeaks, all reminding him of his parents. And at last he is slim and eager enough to travel up the tunnel.

On uncertain feet he makes his ungainly way up the crevice. Skipjack pops his dusky head through the snow covering. The vast world is startling! Blue and white! The sky above snowy slopes teems with low-flying brown squabs—orphans just like him. The air is broadcast with eerie soft calls.

Skipjack tumbles forward, and joyously opens his wings in first flight. Now the sky is home. He may not touch land again until he returns with his mate many months from now. But who will safely guide him over the great sphere of the world to the northern migratory waters?

Skipjack flickers in and out among the adolescent storm petrels. He looks upon the frigid blue Weddell Sea and glides hungrily toward it.

Passing over the ice shelf, he spies a princely south polar skua hanging in the air. Its pale body glistens beneath dark wings, its proud head raised on a neck of golden hackles. A helpless white snow petrol is nipped in its beak. Skipjack banks off, frightened.

He dips to the water, trying the surface. He flutters up and drops back; hovering, dipping his tube-bill to snatch his very first live shrimp. At -10°, he discovers that dining airborne is tasty and bracing. Skipjack makes pass after pass until his belly is finally full.

All about him thousands of storm petrels are swarming, feeding. Among these young flying flocks, Skipjack cruises above the circumpolar ocean.

The days begin dividing in periods of twilight and brief darkness. The untried flocks move northward, reading the sun as they go. Night is defined. A first magnitude star rises and sets. With large sensitive eyes, the birds begin picking their way beneath the moving map of heavenly light. Who has taught them to read the stars?

They approach the thunderous Antarctic-Atlantic convergence. Below them lie abundant krill beds where four blue ballen whales troll and drive. Skipjack flits across great waves, tipping his black bill for his share. Looking into the green depths he sees a great sperm whale wrestling a giant squid.

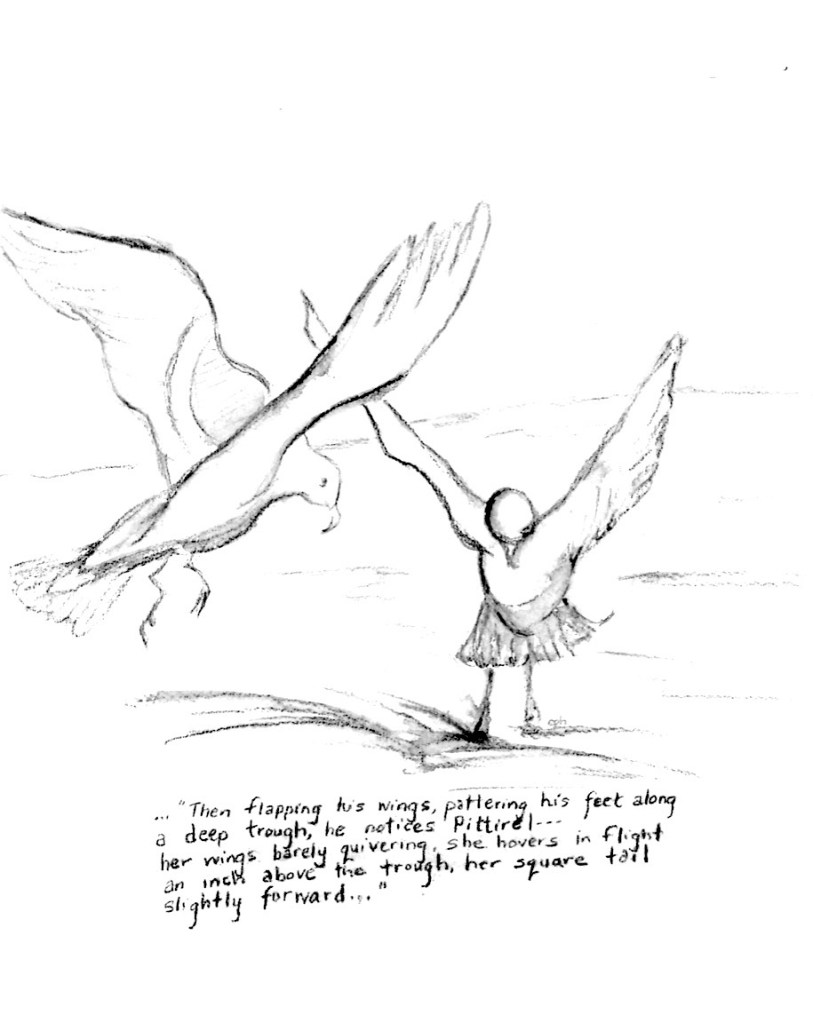

What’s that thing off his right wing? Pattering his feet along the deep trough, he notices Pittirel. He has seen the storm-petrel before. She hovers barely an inch above the trough, her wings a-quiver, her square tail fanned. He sees her dip and pick up a morsel then, hopping, she bounds up a sea green wave. Curious, Skipjack follows.

Seeing him over her back, she flings her head, ridding her nostrils of saltwater. A stinging drop lands in the corner of his eye. He blinks a transparent eyelid to flush it out. “Pit pit pit,” he scolds, and gives up the chase.

Far off the vanished coast of South America, these flocks move northward. They are pelagic—seabirds—shunning the coast whose magnetic fields they sense.

Skipjack’s flock follows a Mediterranean bound merchantman for a whole morning. The clouds scud above them. Brisk winds warn of a coming hurricane. Other followers of the smoking merchant ship include gull-sized sooty shearwaters. They have followed the great circle route around Tierra del Fuego from southern Pacific waters in order to spend the boreal summer in the North Atlantic. Soaring and diving, their wings shear the steep waves as they pick up garbage spilled from the ship’s galley. But the most eloquent companions have fifteen foot wingspans: three dazzling albatrosses looming through the air.

Two men in sou’westers stand at the taffrail on the poop deck. Says Bearded about the albatrosses, “They looks like great ghosts, the way they follows after. See how graceful their feet folds under?”

“Aye,” agrees the mate. “But now look a’yonder at that little birdie, aflying here.” He points to the dusky but white-rumped Skipjack, who flutters up from a trough with something nipped in his beak. “That’s a Mother Carey’s chicken, that is. Called so on account o’how it gets on in the storm. The Holy Mother looks out for’em, or so they say.”

Bearded answers, “I saw one a’hanging in a sailing master’s bunk once. Little thing had a wick down its throat and was blazing away for a lamp. They got some kind of oil in their stomachs, flammable ’tis.”

The men look at the sky. The seas grow steep.

An hour later the storm extends full winds. Rains batter down. The merchantman blunders up on the unruly seas.

Dipping in and out among the leaden-colored, white-foaming seas, Skipjack loses sight of the ship. He tosses on the winds, mothlike, until dark. He patters on the sea like a flamenco dancer. When he is exhausted, winds and rains hammer him into the seas. Again and again he pops up, pumping wings, regaining flight. Day and night it thunders, calming for hours, refraining again in fury. Then the storm wanes, leaving Skipjack to glide out from under, hungry, beaten, used.

Exhausted, he picks up a meal, and another, soon settling down to snooze on calmer seas. He feels a fluttering, looks over to see bedraggled Pittirel, settling to rest close beside. Together the storm birds sleep.

They fly many nights with warm equatorial air currents. The alabastrine stars lead the two birds into the vicinity of Ascension Island.

Skipjack and Pittirel crest a current above the off-island islets. Below them green turtles swim westward toward Brazil. They have left hatchery sands after depositing eggs. Many birds are in the air, mewing gulls and white fragile-looking fairy terns. Northward, a river of red flows between the sides of the sea. Hungry blue whales spout and play, crashing on the waves. Skipjack and Pittirel float down to feast on rich red plankton.

But as they descend something flashes above. A harsh cry startles them. Long-tailed Jaeger, thrice Skipjack’s size, swoops down to take him. Skipjack beats back, his scapular muscles straining. Wings splayed, his pulse rushing, he wheels in the sky.

From above Pittirel shoots a reddish oily stream into the attacker’s face. Skipjack follows suit. They pour the sticky substance over the Jaeger’s eyes and crown. The enemy beats back. “Kreeah!!” He screams, banking in the opposite direction, flying away.

Trembling, the storm-petrels drop down to the wavy red strip of ocean. The Jaeger is forgotten as they feed.

Cloud cover drifts across warm waters, dimming the hot sun rays. As day passes, the flocks reunite and begin moving into misty night dark seas. Peeping and cooing, they call to one another. In the fog there are no starlights to give direction. The birds become confused. They fly in circles or rest on the waves, in danger of being snatched by some hungry predator from below. The days become thick with overcast, but the northward urge persists.

Then, one night Skipjack awakens, blinking at the light of a second magnitude star. Twinkling above the ocean horizon, the star neither rises nor sets.

It brings the flocks to life. Their wings beat a sound of rejoicing as they take off toward the new star.

But each night Skipjack notices that the star is higher. As they approach northward it shines stronger. Polaris of the North has become his guide. A bright asterism, the Big Dipper, rises and sets around it. Ursa Minor revolves around this hinging center. All stars and constellations have this pivotal point for their ordering.

With the star’s aid, Skipjack and Pittirel will hop waves thousands of miles toward iceberg waters—toward Labrador and Ireland, the perimeters of the Arctic. They fly the earth’s sphere to the North, where seals and caribou migrate in spring. The world is always on the move. Its creatures go here and there.

©️ S. Dorman

artist Eileen Hoey

Wonderful story thoroughly enjoyed. Thank you.

LikeLike